Dan Wolff, aka “Tick Man Dan,” specializes in education for the prevention of Lyme Disease and other tick-borne diseases. Good info to remember in tick season as we venture out to shed hunt, turkey hunt, hike to a fishing hole or do deer-habitat work.

Dan Wolff, aka “Tick Man Dan,” specializes in education for the prevention of Lyme Disease and other tick-borne diseases. Good info to remember in tick season as we venture out to shed hunt, turkey hunt, hike to a fishing hole or do deer-habitat work.

Big Deer: Everybody hates ticks. Just what are these nasty things?

Tick Man Dan: Most people think ticks are a kind of insect. They’re not. Technically, they’re classified as arthropods and, more specifically, as acarines, which place them in the same group of bugs as spiders and mites.

Practically, however, what defines ticks is that they are obligate blood feeders (blood is all they feed on). A special feature of most ticks is that they typically stay attached to their host for days or a week to complete feeding; in contrast, mosquitoes are quick-in, quick-out blood feeders. Ticks carry a wide variety of disease-causing germs, and they transmit these agents while blood feeding.

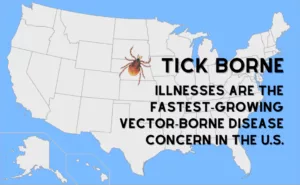

Typically, different species of human-biting ticks are associated with specific disease-causing pathogens. Relatively recent environmental changes, especially expansion of deer populations, have dramatically affected tick ecology and impacted public health in many parts of the United States. To stay disease-free, it’s important for families and individuals to clearly understand their tick-encounter risks and the best practices for preventive solutions.

BD: What diseases do ticks carry?

TMD: As tick populations continue to grow and as tick range expands, scientists are finding a growing list of disease-causing microbes transmitted by ticks. The most well-known is certainly Lyme disease bacteria. Also, Babesia protoza, Anaplesma, Ehrlichia (and other rickettsia), encephalitis-causing viruses and Bartonella bacteria. Heartland virus, which is carried by the Lone Star tick, is spreading across the U.S.

Fact is, while ticks in the past were previously merely an inconvenience, they have become a common carrier of debilitating diseases and must be treated as such.

BD: Okay, we’re wondering, how did you get the name “Tick Man Dan”?

TMD: Back in the early 1990s, I became interested in hiking, hunting and fishing and began spending a lot of time in the woods west of Boston, Massachusetts. I had heard about Lyme disease, but had never thought too much about it until I started finding ticks on my clothing.

In the beginning after time outdoors, ticks seemed few and far between, but in the mid-1990s, something happened–there appeared to be an explosion of deer tick numbers in my area. It seemed that every trip into the woods resulted in being literally covered with ticks. After one afternoon with my golden retriever Champ, I remember pulling more than 250 ticks off him! Lyme disease cases were climbing fast as well as other tick-borne illnesses, and as a father of 2 boys and 2 dogs, my concern was rapidly on the increase.

There were ticks in my truck, my laundry room, on my kids and my dogs and on several occasions, I pulled my sheets back to go to sleep only to discover a tick in my bed.

I became very concerned and started researching ticks like crazy, became obsessed with them. How long have they been around? Do they have some purpose in life? Why are they such an effective vector? How do they bite? How do we prevent them from spreading? What’s the proper tick removal?

As I obsessed about ticks my friends, who thought this fascination was a bit weird, and my social media connections started calling me “Dan the Tick Man.” To me this didn’t flow so well, so I changed it to “Tick Man Dan” and it stuck.

BD: Is there any particular type of habitat that is riskier than others for tick exposure?

TMD: Ticks are found everywhere around the globe with the exception of Antarctica. In the U.S., ticks are mostly concentrated in the Northeast and upper Midwest. These areas have hot temperatures in the summer and cold temps in the winter. Ticks thrive in moist regions and love humid climates.

Ticks can be found in greater numbers where hosts like deer, mice, people and other animals thrive. They are commonly found in the moist leaf litter in wooded or brushy areas. When it’s time to feed, they venture up on blades of long grasses or shrubs and start their questing, or hunting, behaviors.

BD: How should we check for ticks after being outdoors?

TMD: Get naked and do it as soon as you get in from the outdoors. Strip down and put those clothes in a hot dryer for about 15 to 20 minutes. Ticks hate dry heat as much as we hate ticks.

Drag your naked body into a well-lighted room with a mirror. Methodically examine your body head-to-toe, front-to-back. Ticks seem to love hard to reach and see areas of your body, so look closely at the following:

- Between your toes

- Behind your knees

- In your crotch/groin area

- Around your belt line

- In your belly button

- Under your arms

- Back of your neck and behind your ears

Follow the same procedure for your kids.

BD: How much time do we have between a tick getting onto our skin and when it begins biting and feeding?

TMD: Ticks tend to wander around for some time before biting. I have had ticks bite as soon as 3 hours and as long as the next day. Sometimes they will hang out on and in clothing for a while before biting. They seem to search for warm moist body parts before settling in for a meal.

BD: How do you remove an attached tick?

TMD: You want to quickly remove an embedded tick safely and completely. While feeding, a tick is sucking blood through a hollow mouth part directly into its system. Liquid contents of a feeding tick include your blood, its saliva and other fluids. Exposure to any of this is dangerous. Incorrectly removing an attached tick may result in increased exposure to the infectious fluids contained within.

Agitating, squeezing a tick’s body incorrectly, or tearing a stuck tick is bad! All of the above-mentioned methods can result in increased exposure.

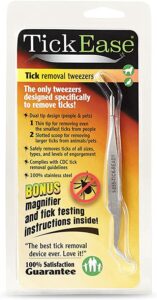

Research shows that the proper use fine-tipped tweezers is by far the best way to remove a feeding tick. Here is an excerpt directly from the CDC’s website:

- Use fine-tipped tweezers to grasp the tick as close to the skin’s surface as possible.

- Pull upward with steady, even pressure. Don’t twist or jerk the tick; this can cause the mouth-parts to break off and remain in the skin. If this happens, remove the mouth-parts with tweezers. If you are unable to remove the mouth easily with clean tweezers, leave it alone and let the skin heal.

- After removing the tick, thoroughly clean the bite area and your hands with rubbing alcohol, an iodine scrub, or soap and water.

- Dispose of a live tick by submersing it in alcohol, placing it in a sealed bag/container, wrapping it tightly in tape, or flushing it down the toilet. Never crush a tick with your fingers.

BD: You created the two-sided Tickease removal tool. Tell us about it.

BD: You created the two-sided Tickease removal tool. Tell us about it.

TMD: No doubt that fine-tipped tweezers are best for removing ticks. The thin, pointy-tipped end of a TickEase tweezer is designed for removing even the tiniest tick nymphs from people. The opposite end of the TickEase with the slotted scoop works great for removing larger ticks and engorged ticks from pets.

BD: Do you have a favorite brand of repellent for ticks?

TMD: In my opinion deet-based products, which work well against mosquitoes and fast-moving biting flies, are not be very effective against slow-moving, slow-breathing ticks. My preference by far is wearing clothing treated with Permethrin. This is to be applied to clothing only and must not be used until completely dry. It is an acaracide which kills ticks that come in direct contact with it even for a short period of time.

BD: To wrap up, what are 3 top tick tips everyone should know?

TMD: Do a thorough tick check every time you come back from being outdoors; put your clothes in a hot dryer for a minimum of 15 minutes after your tick check; remove any attached ticks ASAP and do it properly.

Click here to order Tick Man Dan’s Tickease removal tool ($11.99 or two for $20). Also available from Amazon, where it rates 4.8 out of 5 stars.