Field report from Johnny Sorensen down in Henry County, Alabama:

Field report from Johnny Sorensen down in Henry County, Alabama:

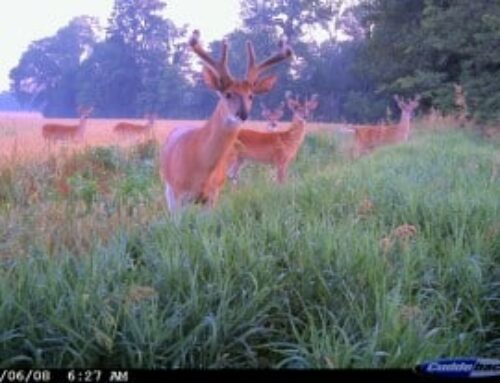

I harvested this 8-point (nearly 17-inch spread with broken brow tine) on December 24, 2021 at approximately 8:00 am in Henry County, Alabama. The deer acted normal in all aspects of a buck in rut. He was emaciated a bit more than you would expect of a rutting buck. I did not weigh him but would guess 120 pounds. As poor as he was, he had obvious signs of fighting and rutting. Multiple bruises about the body were found.

He was first observed traveling through woods on a neighboring property and responded to a doe in estrus bleat. He stayed in the wood line on our property and came to find the “doe” he heard in the food plot I was hunting over. He looked odd. After looking over the food plot he traveled into a clear cut and offered me the shot.

I knew nothing of this bacterial infection until sharing the photo with my friend Eric O’Bryan, who recognized this and informed me of the process to follow per internet articles.

I called Game Wardens Bill Freeman and Joe Carrol, who were unavailable but returned my calls shortly. These men responding on Christmas Eve shows their dedication to their work. Warden Carrol arranged to call a biologist on Monday December 27th even though he knew of no current tracking of a deer with this type of infection.

I disposed of the meat and carcass on the property where the buck was harvested and preserved head on ice pending talking to the biologist. I read where this is a relatively new infection, but I remember a couple of deer like this harvested in my childhood in Dale County, AL.—Johnny S.

Thanks for the story and pictures Johnny and Eric. For more than 10 years BIG DEER has accumulated the largest online database of Bullwinkle, or Big-Nose Deer, and Johnny’s buck is the latest one we’ve seen killed in North America. Interestingly, while we’ve reported on rare and random big-nose deer from Minnesota to Texas to Florida, Alabama is definitely ground zero for the affliction.

Experts we’ve interviewed believe the swollen muzzles of these deer result from chronic inflammation of tissues in the nose, mouth and upper lip. All of the cases studied by researchers in labs so far have shown similar colonies of bacteria in the inflamed tissues.

How and where deer acquire the Bullwinkle bacteria is unknown. “It’s not like anything else we’ve seen in deer,” said Kevin Keel, associate professor at the University of California–Davis school of veterinary medicine and the nation’s leading expert on the disease, and with whom I’ve corresponded on this topic numerous times. “This is an interesting disease because we’re not sure if it’s new. It might be something that’s always occurred in deer, but at such a low prevalence that maybe it was always there, we just didn’t know about it.

According to the Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study (SCWDS) at the University of Georgia, which has done by far the most research on this malady, Bullwinkle disease has only been known to exist since 2005; no cases appear in 50 years of SCWDS files prior. Scientists are unsure of this is because the disease has only been around for 17 years, or because hunters from across the country can now share photos of their big-nose deer kills on social media and websites like BIG DEER, bringing more and instant recognition of the disease.

While Bullwinkle doesn’t appear to be fatal to deer, Keel notes that many animals, like Johnny’s deer, with the chronic bacterial infection suffer weight loss that weakens the animals. Keel adds that since most cases of the disease are random, “It doesn’t seem to have any impact on overall populations.”

Number 1 question we get: Is a deer with a swollen nose safe to eat? In a word, NO. Scientists say the long-term nature of the infection could mean that bacteria are present in the blood and muscle of the meat, or a secondary infection could also have developed. This is exactly what was found in this Bullwinkle doe from Minnesota. Johnny was smart to dispose of the carcass safely.

He was also smart to call a Game Warden and preserve the head of his buck so it can be studied by scientists. If you or anyone you know shoots one of these rare deer, be sure to report it to authorities and send us photos and the story for our Big Nose database.