I just returned from shooting an Axis deer TV show in the western Hill Country of Texas. During my hunt, daytimes temperatures ranged from 95 to 100 degrees. I was struck not only by the heat, but the incredibly dry and brown country. It hadn’t rained measurably in months, and the habitat showed. The 2 bucks we shot were beautiful animals (mine pictured below, shot near a waterhole), but noticeably smaller and less body heavy than they would have been in a year of normal precipitation. It got me to thinking about how a drought affects deer.

I just returned from shooting an Axis deer TV show in the western Hill Country of Texas. During my hunt, daytimes temperatures ranged from 95 to 100 degrees. I was struck not only by the heat, but the incredibly dry and brown country. It hadn’t rained measurably in months, and the habitat showed. The 2 bucks we shot were beautiful animals (mine pictured below, shot near a waterhole), but noticeably smaller and less body heavy than they would have been in a year of normal precipitation. It got me to thinking about how a drought affects deer.

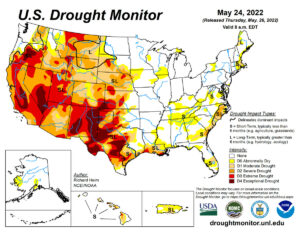

As you can see by the map, much of the western half of the country is experiencing moderate to severe drought conditions, and some regions have been dry for months and even years. In this article Covy Jones, big game coordinator for the Utah DWR, discusses how abnormally dry conditions affect deer and their habitat. While Covy talks specifically about his state’s mule deer, his information pertains to whitetails as well in hard-hit drought areas like Texas, western Oklahoma and Kansas, the Dakotas, Montana and Wyoming. Here are some main takeaways from Covy’s analysis.

When there is insufficient moisture, plant growth is stunted and plants also lack the nutrition that deer need for survival and reproduction. Without proper nutrition in spring and summer, deer will not gain the necessary fat reserves to make it through the winter. Malnourished deer are less likely to survive and successfully reproduce.

Drought conditions make the new spring growth on shrubs harden faster than usual, limiting a deer’s ability to eat and digest it effectively. If shrub growth is insufficient or too tough to eat, that can be a problem for deer, who ideally need to build up their fat reserves during summer and fall. Having adequate body fat is one of the key factors determining whether mule deer (and whitetails) survive the winter or not.

During drought conditions, fawns are born smaller and grow more slowly than during wetter periods. If fawns do not reach a sufficient size and weight prior to winter, they will not have enough energy reserves to make it through, especially if the winter is severe.

For does, drought can lead to poor body condition and result in these possible outcomes: stillborn fawn births, low fawn birth weight, poor newborn fawn survival, inadequate milk supply to nourish a fawn. Sometimes, a doe will carry a fawn full-term and raise it, but the newborn is much smaller than a fawn born in a non-drought year. Smaller, weaker fawns are less likely to survive their first winter, especially if conditions are harsh. Milk production (lactation) is also very demanding on a doe’s body. If drought affects a doe’s milk supply, that can lead to decreased survival of newborn fawns during both the summer and winter months.

During drought years, bucks will not have surplus nutrition to grow antlers as large as they might in a non-drought year. They will still produce antlers — and they may be big — but perhaps not as big as they would grow during a year with good precipitation.

In the photo: Shot this great Axis buck in velvet near a waterhole last week on a 104-degree afternoon. It was the first animal I have shot with my new CZ 600 bolt-action chambered in .30-06.

In the photo: Shot this great Axis buck in velvet near a waterhole last week on a 104-degree afternoon. It was the first animal I have shot with my new CZ 600 bolt-action chambered in .30-06.